Videos

Script

1 Good morning, everyone, my name is Runxin!

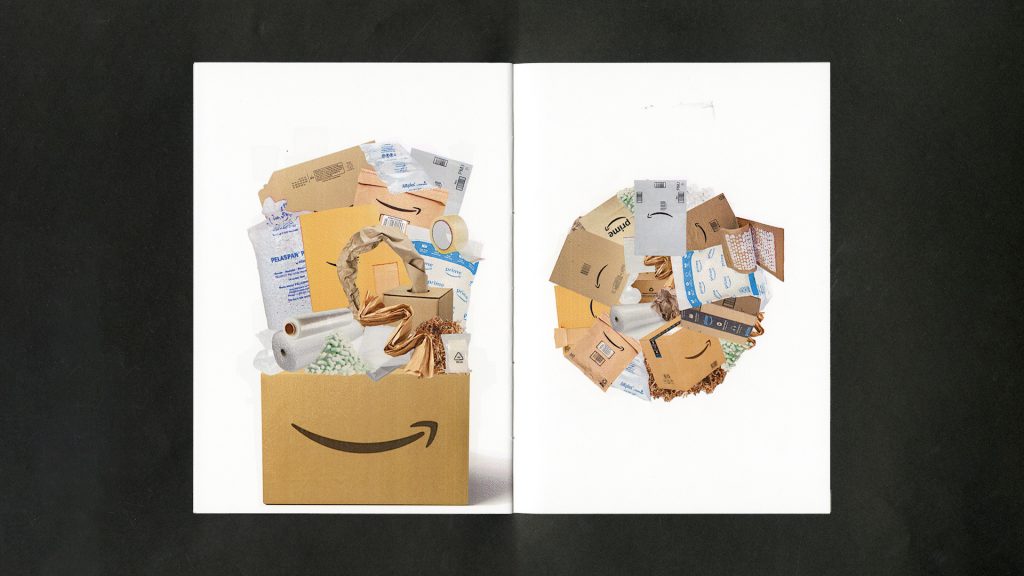

Have you ever stopped to think about what happens to the things you throw away? This soda can, that shipping box from your latest online order – what becomes of them after they leave your hands? Recycling often feels like the end of the story, but what if I told you it’s just another chapter in a much bigger and more complicated system? Today, I want to explore this hidden world, focusing on an often-overlooked material: cardboard.

2 In the first half of my Unit 2, I explored the purposes of recycling. So, what does recycling really do?

3 Recycling may seem like a solution to waste, but according to Discard Studies, it’s actually just another way of discarding.

4 It gives us a ‘responsible’ place for waste, so we can keep producing and consuming disposable products – making this cycle feel morally acceptable. This ‘green’ image, built by recycling, ultimately enables waste and overproduction to continue.

5 So, what does this system of production look like then?

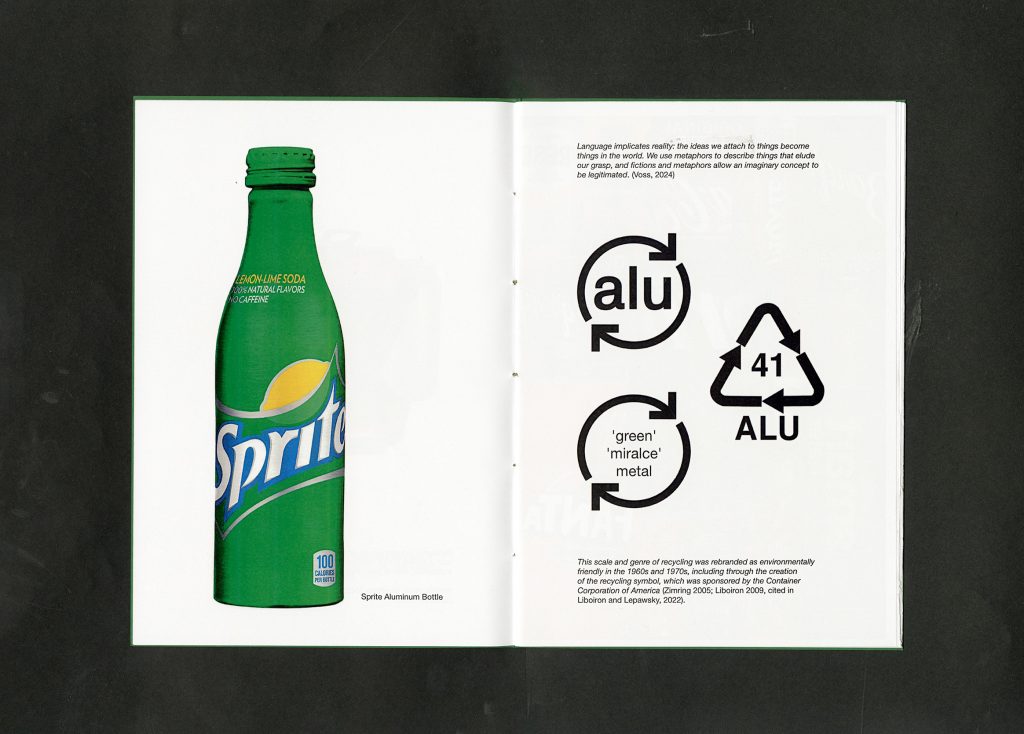

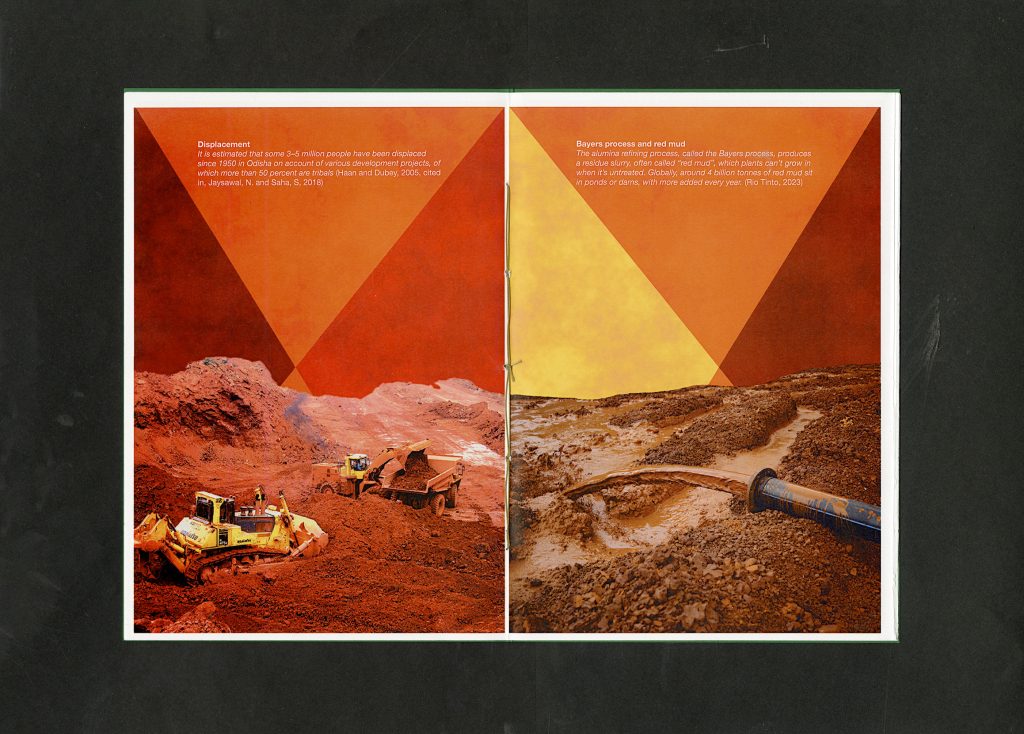

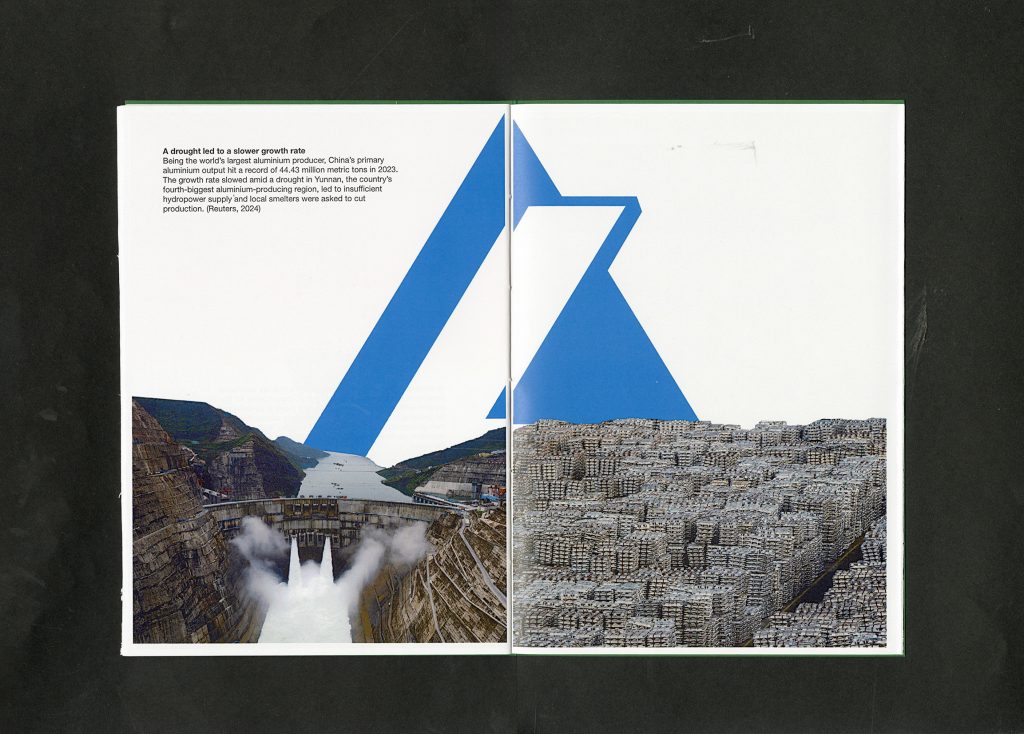

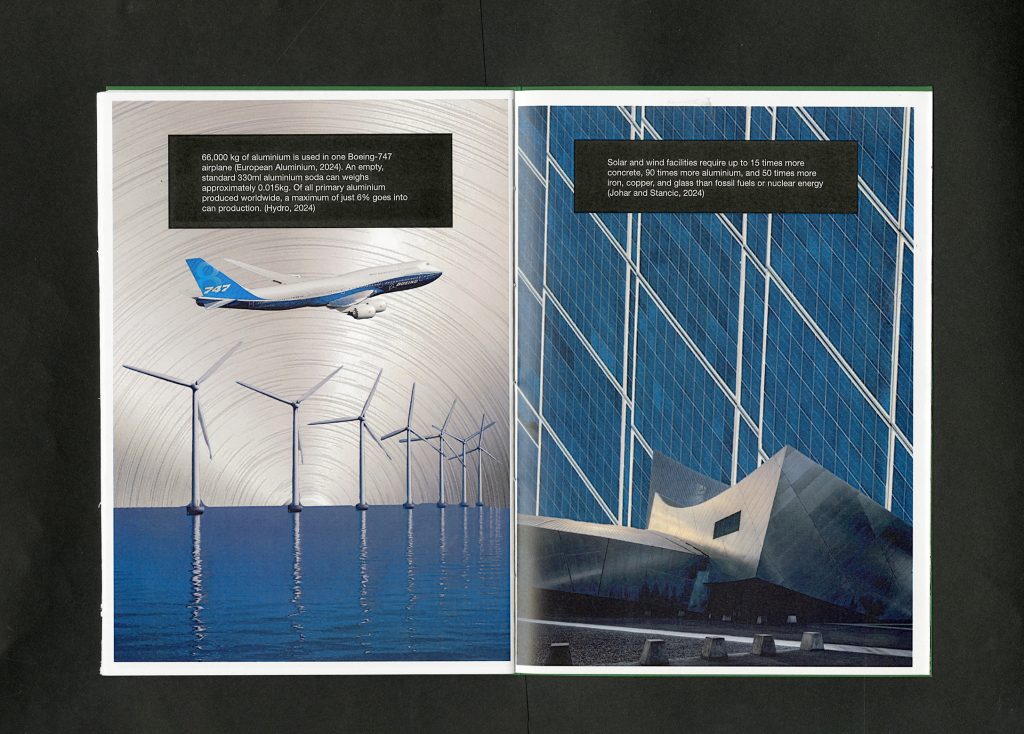

6 This Sprite can is made from recycled aluminium and can be recycled again, but that doesn’t eliminate the need for ongoing metal extraction, pollution caused by mining, or the energy required to produce new aluminium – used in everything from our digital devices and airplanes to modern buildings and renewable energy stations.

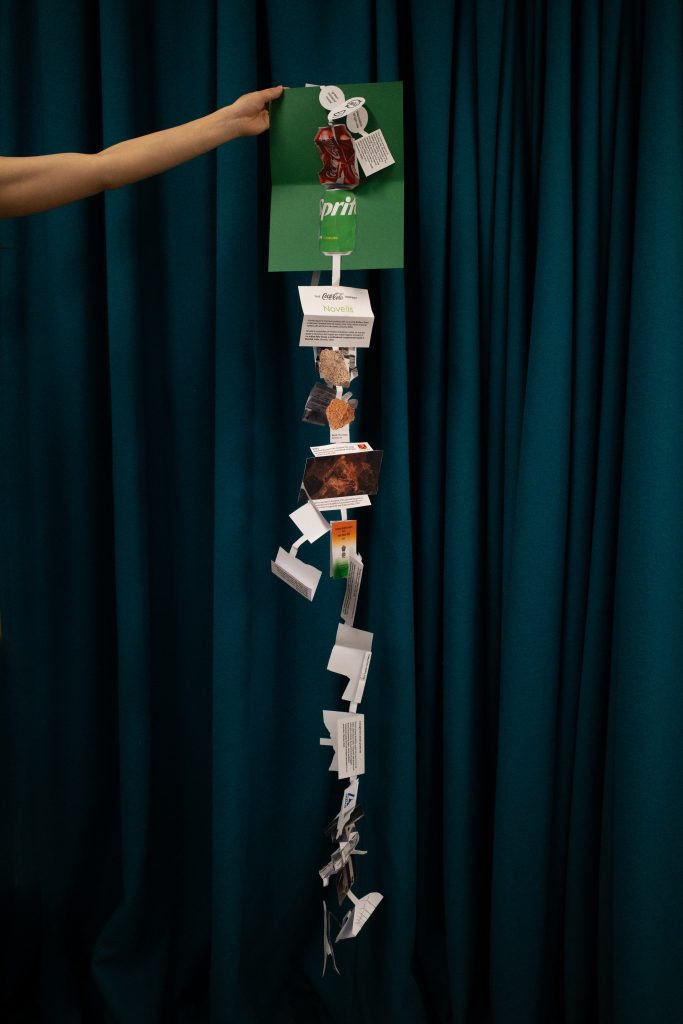

Ultimately, everything you see here, including this recycled Sprite can, serves the same dominant companies and the industrial system of production.

7. It’s still pretty complex, right? How do I make this system more tangible?

8 One of my attempts is a folded publication, mapping the aluminium industry, helping viewers experience its complexity.

9 However, printed images still lack a sense of embodiment. Aluminium, as a strong, industrially processed material, was difficult to manipulate without specialised tools or expertise. This led me to shift my focus to corrugated cardboard – a primary packaging material that is more modifiable but equally tied to systems of production, consumption and recycling.

10 Interestingly, the recycling symbol was actually commissioned by the Container Corporation of America, a cardboard manufacturer, on the first Earth Day in 1970. Since then, large volumes of cardboard have been produced and consumed, benefiting from its reputation for being highly recyclable. This paradox highlights cardboard’s unique role in our growth-driven society, making it an ideal material for examining issues of consumption, waste, and sustainability.

11 This brings me to a fundamental question about cardboard’s role in society.

Barthes once said that even the simplest everyday objects can reveal deeper truths about society when we examine them closely.

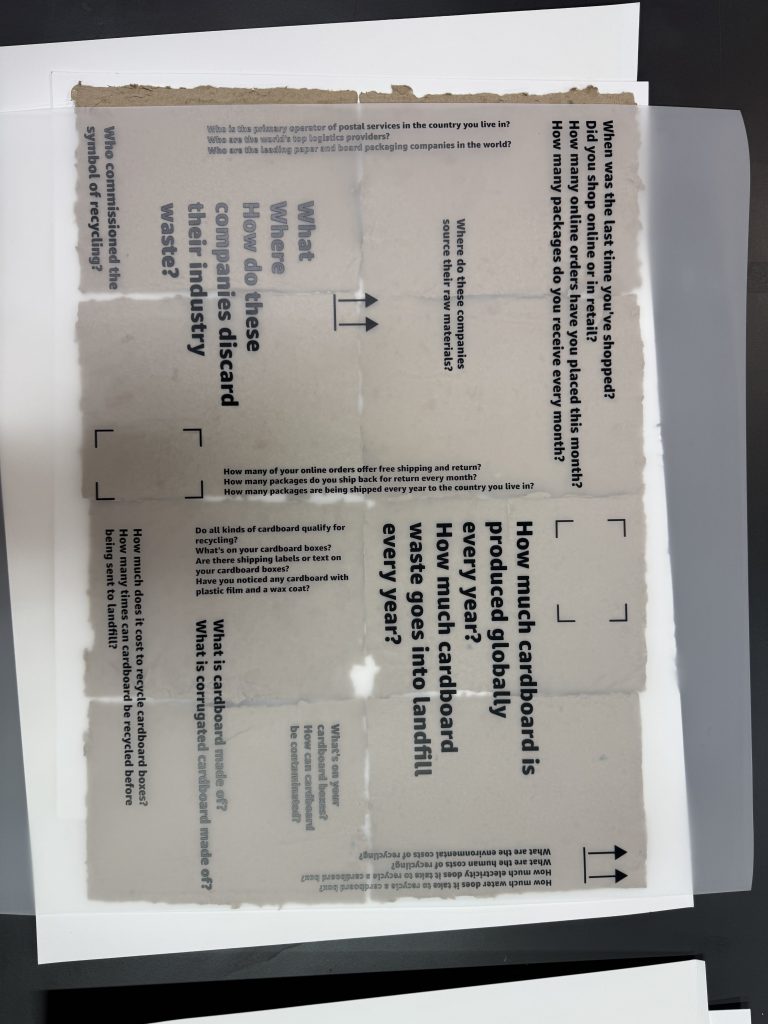

12 So, what can a cardboard box teach us about recycling and production systems?

13 My first approach was to deconstruct a double-wall corrugated cardboard box and remake it into A5 paper sheets.

14 Through this process, I realised that recycling involves significant resources, like water, electricity, and labour, and it generates hidden by-products like polluted water and microfibres. These are all part of recycling, yet they’re often unaccounted for within the system.

15 At this stage, I still cannot solve the waste problem or fully grasp the recycling system, but I do have questions.

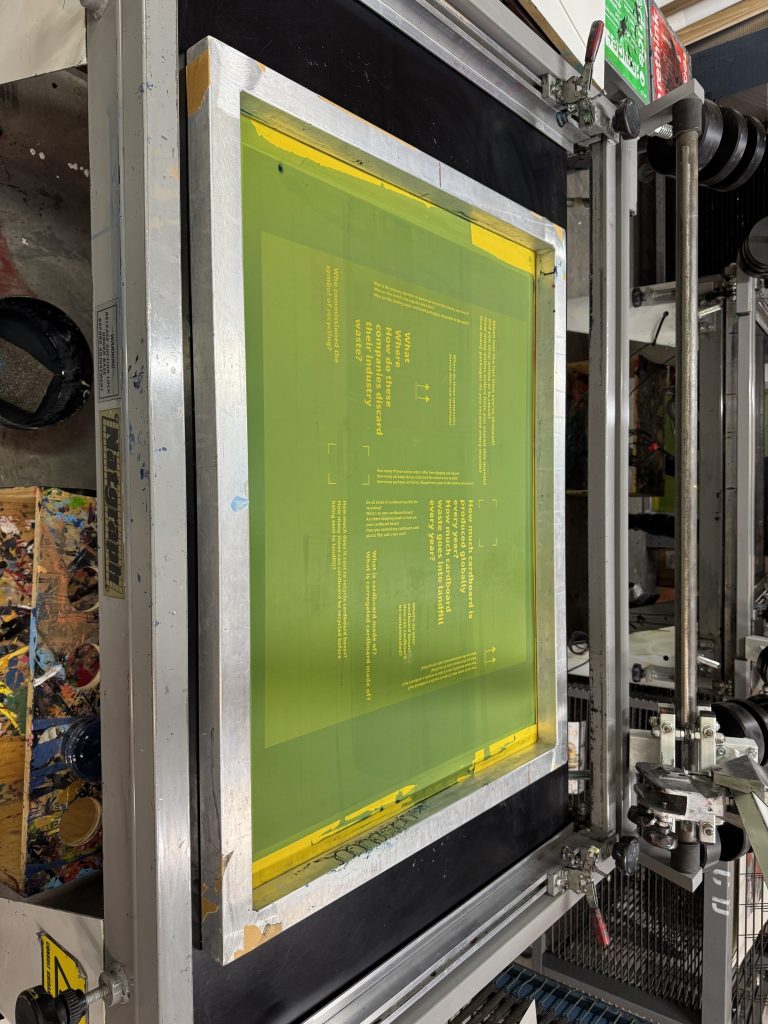

16 This brings me to my second approach: storytelling through questioning. These 101 questions are not about finding definitive answers but initiating dialogues, encouraging reflection and sparking curiosity about cardboard’s journey.

17 Because I wanted to create an experience that mirrors these systems, I explored an alternative way to publish my findings.

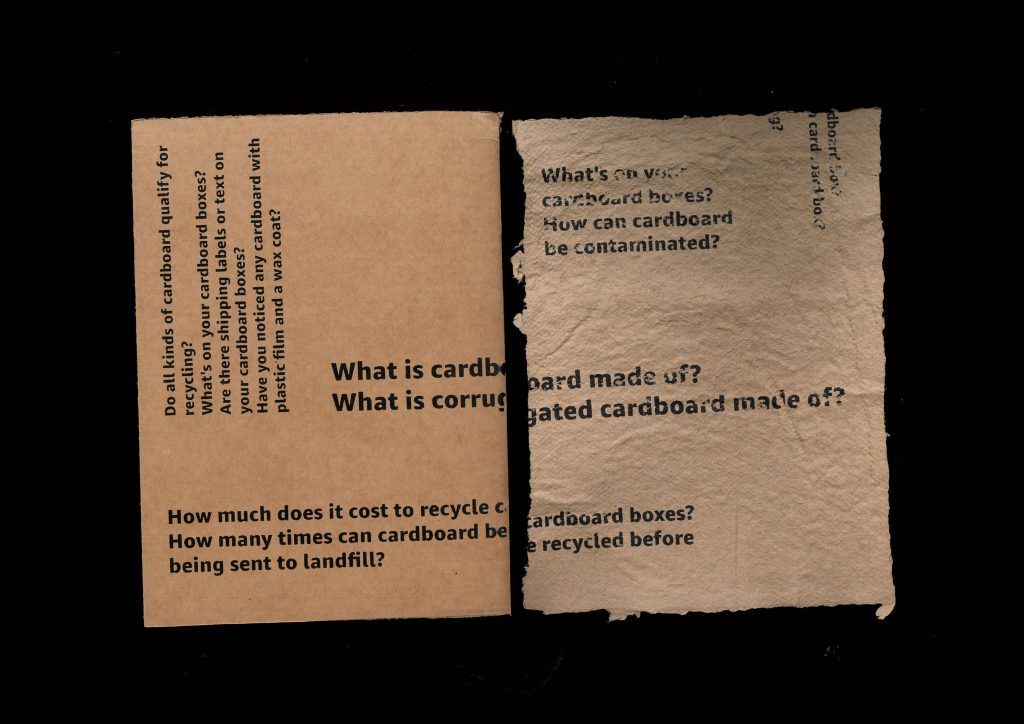

18 I examined a cardboard box’s labels, text layout, and silkscreen printing techniques. Then I screen-printed selected questions from my previous publication onto the recycled paper and corrugated cardboard sheets.

19 The audience may need to piece these pages together like a puzzle to uncover the full message, though some letters are intentionally missing in the gaps.

20 These gaps represent the unseen costs, waste and by-products often overlooked in recycling and production systems.

21 Individually, we rarely see the whole picture of these impacts.

22 My personal attempts to recreate the industrial processes of recycling and paper production revealed the limitations of working without the resources, knowledge, and access that corporations have. Despite my efforts, I couldn’t fully grasp the system as a whole, which supports Voss’s argument that scale is a process used to justify an unequal distribution of power and resources (2024).

23 Early in our course, we were introduced to the idea of “thinking through making”, which I initially found challenging – I didn’t believe that design could happen intuitively. However, by physically transforming cardboard on a domestic scale and publishing various graphic design outcomes, I was able to highlight the contradictions and limitations in the recycling process, making them more tangible and bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and sensory experience.

24 So, what’s next? I want to explore cardboard from an ecofeminist perspective, examining the invisible and often unevenly distributed labour, especially the female workers involved in cardboard production, application, and recycling. Could this undervalued, taken-for-granted material also carry insights into feminist enquiries? That is the question I will explore next.

Images